July 7-9, 2013

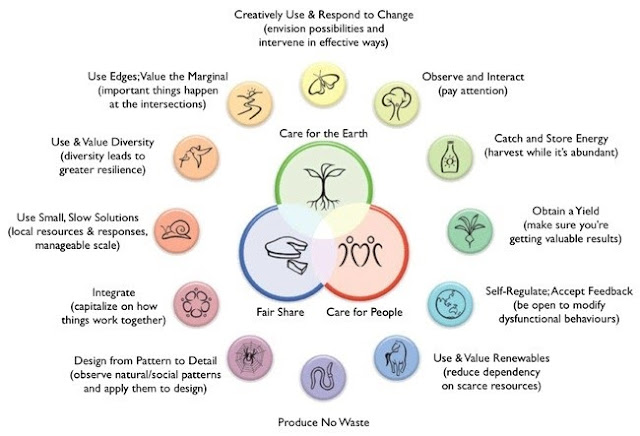

I am trying to write quickly before the sun goes down. I am in Longido, a small town close to the Kenyan border in Northern Tanzania, situated in a Maasai village a few kms outside of town. The sun is going down behind the boma (traditional Maasai mud huts) and this is by far the most memorable thing I’ve done in Tanzania so far. I am here with an Australian-based NGO called Testigo Africa (Testigo means “witness”), which is currently teaching Maasai women permaculture agriculture principles. Permaculture refers to a set of sustainable and ecological design principles, really, that can be applied to a variety of areas such as landscaping, architecture, and gardening (and if scaled up, farming, which is a possibility I am still looking into). To date, Testigo has trained about 120 individuals in the area in permaculture techniques, around 100 women and 20 men.

Longido Mountain towers behind the bomas and is absolutely breath-taking. It is so peaceful here, with only two families and the occasional moo of a cow, squawk of a chicken, or hee-haw of a donkey. Although the Maasai men are traditionally polygamous, there are only two families here because the “man of the house” only took two wives. As you enter the gate to the village, the first wife lives on the right and the second on the left. If he had more wives, he would continue to alternate their bomas: right-left-right-left. Today was absolutely incredible. The Maasai are traditionally pastoralists and keep livestock, so of course, I learned how to milk both a goat and a cow, however, rather unsuccessfully. I kept feeling like I was going to hurt it, though I found the cow to be a lot easier and much more fun: a bigger udder means more to hold onto, so to speak. I drank the best tea of my life as well – they boil the milk and steep the leaves directly and add cinnamon, sugar, and cardamom – so rich and complex in flavor. My taste buds were doing somersaults during these few days.

Interview with Ndoya:

I was able to interview a local woman named Ndoya, who was trained in permaculture and proceeded to become a trainer herself. Ndoya is twenty-six-years-old and the mother of two. She first got into farming and permaculture because she “liked the idea of it.” She has been cultivating vegetables for about 8 months, since she was first trained by Testigo. She enjoys eating vegetables and before growing her own, she would have to buy them, which was quite expensive. Ndoya expressed how at first, horticulture was rather difficult because it was very different from the domestic and livestock activities she was doing before and it required a lot of initial preparation. She began with two double dug beds and gradually increased to a key-hole garden and also a sack garden. She grows nightshade, kale, and Chinese cabbage to name a few vegetables, and can order seeds from Arusha and then save them for future seasons. Incredibly, she’s made more than 100,000 tsh (~$63 USD) in the first two months of selling produce. When asked about water, apparently people in town take turns fetching water and each woman collects 200 liters per week, once a week. Since she has established herself a bit more economically, she is now able to pay other people to carry the water for her. And after having been trained in permaculture, she started training others for additional income generation. I asked Ndoya about some of the challenges she’s facing as a small-scale producer and she noted how, in preparing her own garden, acquiring manure was quite difficult because she doesn’t keep her own cows. To complicate matters, the local Maasai were selling manure to a biogas company, which raised the price for other buyers. Unsurprisingly, drought has posed a consistent challenge and with regard to pest control, she has been using ash and natural herb plants instead of chemical inputs and to fend off birds, she guards vegetables with acacia branches with are obscenely thorny. Her practices are entirely organic, using a closed loop system of animal waste as fertilizer. And back to the issue of gender, Ndoya also found it difficult to train fellow women due to their own domestic duties, which often caused them to miss training sessions. The women, however, have been able to share hand tools such as shovels and hoes among each group of 20. Ndoya’s mother, who lives with the family, was excited about the prospect of permaculture because she wasn’t able to afford vegetables beforehand because they had to be trucked in from Arusha (about an hour away). Using the proceeds from the vegetable sales, they were able to buy dishware and a kerosene stove. Now, they have eight double dug beds, and of the three types (double dug, key hole, and sack), they prefer key hole gardens because they don’t require as much water, can use waste water (e.g. soapy from dishes) because of the filtration mechanism, and give a higher yield. In the future, they hope to recycle an old mosquito net and use to protect the key-hole garden vegetables from pests.

Interview with Namnyak:

Namnyak has two children and has been living in this village for more than five years. She began cultivating vegetables when Testigo Africa introduced the idea and convinced her to start her own garden. Testigo first got involved in the area through the implementation of a community water project. Namnyak grows vegetables for both home consumption and also sales, having made 70,000 tsh (~$44 USD) so far, which has helped her pay for her son to go to school in Arusha. Namnyak hopes to continue gardening and wants to expand her business and sell higher volumes at the market, in addition to starting another business (to be determined). With regard to challenges that she faces, in Maasai culture, women do not own the livestock; their husbands do, so naturally, she wants to save her money to invest in her own animals. When asked about mobile phones and how they have/haven’t helped her business, she explained that customers can ring her for produce delivery, she can be called and told when tourists are passing through town (the women all flock with their beads for sale), and when livestock goes missing, she can ring her husband to find them. This was a bit shocking to me, the way people prioritize their funds and choose "material luxuries." For instance, these women don't have running water or electricity, but they have cell phones. And in addition to a phone, she has a radio, which she was informed could provide her with information on good agriculture practices.

Today was absolutely magical. Parts of it even brought tears to my eyes. After a horrible night’s sleep at the guesthouse in town (really it was more like a budget hostel where I slept in a concrete cube of a room with a drop latrine that was detached from the building), I woke up at 5:45 AM. We were going to go on a walking safari at 6:30 in the morning. We walked for 2.5-3 hours through the bush, weaving in and out of acacia trees and trying to avoid being slashed open by the deadly branches coated in thorns. On the ground level, spikey protrusions greeted our legs and made one regret bearing any skin, even a patch of ankle, because of the angry burrs. Despite these botanical death traps, the walk was glorious. We set off at a “Maasai pace” (aka speed walking); I think it was the most exercise I’ve gotten in Tanzania so far (I can’t really count doing yoga, squats, and running in place in my room…). Although we didn’t see any animals, except for the occasional bird and a hare, the sun was rising and the landscape seemed to go on for miles in all directions. Apparently, we didn’t see any animals because they have been illegally hunted by non-Maasai who have moved into the area. It’s really quite sad, as elephants, giraffes, and zebras used to roam the grasslands right outside the village. The pastoral Maasai have been living in “harmony” with the wildlife for years and now the animals are being killed for their meat, which can be sold in Arusha, in addition to their ivory and hides.

After the walk, we came back to the most-welcomed cup of tea and chapati (little pancakes) – yum! After a later lunch, we rode a truck into town and as I was sitting in the bed, a young boy hopped in the back, and we started chatting. I greeted him with the usual “mambo” (a slang salutation used among young people) and was surprised when he answered in perfect English. It turns out that he is fifteen or sixteen and is well known in town because a mzungu adopted him eight years ago and this is his first time back. He hardly knows the language and is apparently offending people left and right because of his pierced ears (which is the utmost insult because it’s womanly) and the fact that he was circumcised in a U.S. hospital. I learned that circumcision is a tremendously important right of passage for Maasai males and it is very likely that his community will ostracize him forever. I know all of this info from my hosts, naturally, and learned only a bit about him from our truck talk: he is attending a prep school in Vermont and has played hockey against Williston-Northampton School, which was shocking, since he too has been in my hometown in Massachusetts. Sometimes the world is frighteningly and excitingly small.

While in town, my hosts and I each got sour milk, which is customary for Maasai culture. It sounds off-putting and potentially disgusting, but it was fantastic, like drinking tangy Greek yogurt, except that it had some creamy chunks; really it was an ice-cold “milkshake” for only 1,000 tsh ($0.63 USD).

.jpg)

After we returned to the village, I helped milk again (still unsuccessful) and even assisted with preparing dinner. This was by far the most emotional part of my day. It started when we were sipping chai as the sun was setting and Ngai, one of the daughters, walked by with a bucket of spinach freshly picked from the garden. I asked if I could come watch and help. “Hodi” I called out (may I come in) as I entered their boma. “Karibu” (welcome). I walked into the kitchen, which was really just a three-stone stove in a corner of one of the mud huts. Two older Maasai women were there, Namnyak (one of the wives), Ngai, Sokoina (her brother), and four children. Despite the cramped nature of the hut, they offered me a miniature wooden stool on which to sit. The boma was really dark (no windows) and sickeningly smoky (no chimney and a face-full of carcinogenic fumes). I don’t understand how it doesn’t bother them, but I later learned that the smoke helps treat the wood against termites. At first I just watched as Ngai peeled potatoes and Namyak shredded something over the fire. Then I was asked if I wanted to help, so I took a knife in hand and began peeling a potato. Naturally, the whole room was enthralled by my show of incompetence and goofiness. At home, we have a potato peeler and a cutting board. Here, I had a dull knife and my knee. Fortunately, I’ve been trying to help Helen with meal preparation at my homestay, which has assisted in weaning me off a peeler, but it is still more difficult than it looks (as illustrated by the massive slice I made in my thumb last week). So the Maasai all watched with intrigue as I switched on my head lamp (goofy sight #1) – I don’t know how they cut in the dark with a single flicker of candle light. I was slow and keep peeling too thickly. They must have thought I was such a lazy, wasteful, and inept American; I was embarrassed. But I tried because I want to learn and get better. Ngai has been cooking since she was ten; now she’s my age. I guess this partially explains her swiftness, accuracy, and dexterity in the kitchen. I helped her cut the spinach into shreds, not realizing how much a cutting board is a crutch back home. Only about two people in the room spoke broken English, the rest Maa and Swahili. The women were adorned with ornate beaded jewelry, hanging around their necks and drooping gauged ears. I must have looked so out of place, yet I felt strangely at peace. I could barely communicate with them, but chopping vegetables, it didn’t matter. Then came the signing. Sara, a beautiful young girl no older than 8, often sang for us. Then they asked me to sing a song from home…jokes! Anyone who has heard me belt a tune knows it ain’t pretty. I froze up and couldn’t think of a song to save my life, as if all known lyrics dissipated from my brain immediately. Frantically and randomly, I squeaked (out of tune and pitch, mind you) the lyrics to “Wagon Wheel” by Old Crow Medicine Show. A stereotypical camp song and a quintessential anthem of Hamilton, I belted out:

“Rock me mama like a wagon wheel. Rock me mama any way you feel. Hey, hey, mama rock me. Rock me mama like the wind and the rain. Rock me mama like a south-bound train. Hey, hey, mama rock me.”

I don’t think they had a clue what the lyrics meant, which is probably for the best, but they seemed to enjoy it because it had “mama,” a universally recognized word. I received a warm round of applause at the end. Sitting in the boma, smoke burning my eyes, surrounded by Maasai women and children, I felt like I was in another world. It was so different from anything I’ve experienced, so strangely beautiful that it brought tears to my eyes (or maybe it was the smoke). I think these are the moments that the foundation refers to: profound and serendipitous instances of cross-culture human connection. And I don’t think it could have been more fitting than through food and cooking. I feel so different from these people: at the age of 3 or 4, young boys are out herding cattle; women must walk several miles to fetch water daily and sometimes they are forced to marry at a young age. They live in mud huts without running water or electricity, yet they seem at peace (though perhaps this is an extremely narrow minded and ignorant judgment). Though I can say with certainty that the stars here are the most amazing I have ever seen…like someone took the top off the sky and sliced open the atmosphere, scattering diamond dust; the stars have multiplied in number and luminosity as well, with very little surrounding light pollution. I can hear the faint sounds of the cow bells jingling and the occasional snort or sneeze of the livestock from the mud guest hut I am sleeping in.

My hosts here have been incredibly generous. They invited me to observed and partake in activities that most people would pay big bucks to do: learning how to milk, going on a bush walk, sleeping in a Maasai boma etc. I am just beyond grateful for their hospitality and also inspired by their good will. The woman used to be a lawyer, working for big firms around the world, London, Hong Kong etc. and after eventually establishing Testigo Africa, she is now doing what she loves. Her husband is Maasai, originally from around Ngorongoro Crater and is now training street boys in football (soccer) to help them reach their fullest potential. Her husband and I engaged in a variety of discussions ranging from corruption to the organic food movement. According to him, we need good governance if real change is going to occur, as it must be policy-based. I agree with him, but I also think that we cannot overlook the potential for grassroots action to make a significant impact. I think it has to come from both the bottom up and top down, meeting somewhere in the middle. He noted how in Tanzania, land is the problem. Organic agriculture is wonderful in theory but if they’re not applying chemical inputs, they still need natural solutions such as livestock manure. Unfortunately, it is becoming more and more difficult to raise livestock because of climate change (increased drought and decreased grasslands) and overall, decreasing land availability.

During my last day in Longido, about 30-40 Maasai women from nearby villages came together to exchange ideas about permaculture. We took a tour of the demonstration training plot, which aims to show what can possibly be grown under these harsh conditions (dry, sunny, sandy soil). According to my hosts and the translators, permaculture is self-defined, though in general, it can mean being able to utilize small spaces to grow as much as possible, especially using sustainable practices such as companion planting and nitrogen-fixing crops. It also emphasizes the use of everything available and planning systematically and in layers. The demo plot is only a little more than ½ an acre, but they are able to grow 20 different types of crops and also utilize some terrace farming to help maintain water. They explained how to prepare double dug beds, which are just raised mounds/rows for planting (either prepare compost using food remains and grass; OR collect manure, dry it in the shade for 10-14 days, and then mix it with soil to add nutrients; OR you can use vermicompost from worms (however, the volume is usually insufficient in itself). In the demo plot, they are growing spinach, Chinese cabbage, kale, beans, papaya, pigeon peas, maize, sweet potatoes, and neem trees. The use chili, ash, lemongrass and neem as natural pesticides and intercrop (e.g. sunflowers with maize, which helps the soil nutrient levels). I learned that moringa has 7x as much potassium as bananas, 10x as much vitamin C as oranges, 15x more protein than an egg; and you can dry it and make powder as a dietary supplement (which is what we did at my homestay), especially good for people with HVI/AIDS . What’s more is that moringa grows well even in dry areas. They stressed that a moringa tree should be planted in every dispensary and boma. In addition to the double dug beds, they also have a keyhole garden and a plastic-lined dam, which collects and stores water twice a year during the rainy season. Overall, the day seemed effective in facilitating the exchange of information and ideas among different women’s groups. Hopefully, it led to the creation of new visions and shown some of the challenges (e.g. on raising chickens and cultivating vegetables).

Goodbyes

I am trying to write quickly before the sun goes down. I am in Longido, a small town close to the Kenyan border in Northern Tanzania, situated in a Maasai village a few kms outside of town. The sun is going down behind the boma (traditional Maasai mud huts) and this is by far the most memorable thing I’ve done in Tanzania so far. I am here with an Australian-based NGO called Testigo Africa (Testigo means “witness”), which is currently teaching Maasai women permaculture agriculture principles. Permaculture refers to a set of sustainable and ecological design principles, really, that can be applied to a variety of areas such as landscaping, architecture, and gardening (and if scaled up, farming, which is a possibility I am still looking into). To date, Testigo has trained about 120 individuals in the area in permaculture techniques, around 100 women and 20 men.

Permaculture design principles

Longido Mountain towers behind the bomas and is absolutely breath-taking. It is so peaceful here, with only two families and the occasional moo of a cow, squawk of a chicken, or hee-haw of a donkey. Although the Maasai men are traditionally polygamous, there are only two families here because the “man of the house” only took two wives. As you enter the gate to the village, the first wife lives on the right and the second on the left. If he had more wives, he would continue to alternate their bomas: right-left-right-left. Today was absolutely incredible. The Maasai are traditionally pastoralists and keep livestock, so of course, I learned how to milk both a goat and a cow, however, rather unsuccessfully. I kept feeling like I was going to hurt it, though I found the cow to be a lot easier and much more fun: a bigger udder means more to hold onto, so to speak. I drank the best tea of my life as well – they boil the milk and steep the leaves directly and add cinnamon, sugar, and cardamom – so rich and complex in flavor. My taste buds were doing somersaults during these few days.

Interview with Ndoya:

I was able to interview a local woman named Ndoya, who was trained in permaculture and proceeded to become a trainer herself. Ndoya is twenty-six-years-old and the mother of two. She first got into farming and permaculture because she “liked the idea of it.” She has been cultivating vegetables for about 8 months, since she was first trained by Testigo. She enjoys eating vegetables and before growing her own, she would have to buy them, which was quite expensive. Ndoya expressed how at first, horticulture was rather difficult because it was very different from the domestic and livestock activities she was doing before and it required a lot of initial preparation. She began with two double dug beds and gradually increased to a key-hole garden and also a sack garden. She grows nightshade, kale, and Chinese cabbage to name a few vegetables, and can order seeds from Arusha and then save them for future seasons. Incredibly, she’s made more than 100,000 tsh (~$63 USD) in the first two months of selling produce. When asked about water, apparently people in town take turns fetching water and each woman collects 200 liters per week, once a week. Since she has established herself a bit more economically, she is now able to pay other people to carry the water for her. And after having been trained in permaculture, she started training others for additional income generation. I asked Ndoya about some of the challenges she’s facing as a small-scale producer and she noted how, in preparing her own garden, acquiring manure was quite difficult because she doesn’t keep her own cows. To complicate matters, the local Maasai were selling manure to a biogas company, which raised the price for other buyers. Unsurprisingly, drought has posed a consistent challenge and with regard to pest control, she has been using ash and natural herb plants instead of chemical inputs and to fend off birds, she guards vegetables with acacia branches with are obscenely thorny. Her practices are entirely organic, using a closed loop system of animal waste as fertilizer. And back to the issue of gender, Ndoya also found it difficult to train fellow women due to their own domestic duties, which often caused them to miss training sessions. The women, however, have been able to share hand tools such as shovels and hoes among each group of 20. Ndoya’s mother, who lives with the family, was excited about the prospect of permaculture because she wasn’t able to afford vegetables beforehand because they had to be trucked in from Arusha (about an hour away). Using the proceeds from the vegetable sales, they were able to buy dishware and a kerosene stove. Now, they have eight double dug beds, and of the three types (double dug, key hole, and sack), they prefer key hole gardens because they don’t require as much water, can use waste water (e.g. soapy from dishes) because of the filtration mechanism, and give a higher yield. In the future, they hope to recycle an old mosquito net and use to protect the key-hole garden vegetables from pests.

Interview with Namnyak:

Namnyak has two children and has been living in this village for more than five years. She began cultivating vegetables when Testigo Africa introduced the idea and convinced her to start her own garden. Testigo first got involved in the area through the implementation of a community water project. Namnyak grows vegetables for both home consumption and also sales, having made 70,000 tsh (~$44 USD) so far, which has helped her pay for her son to go to school in Arusha. Namnyak hopes to continue gardening and wants to expand her business and sell higher volumes at the market, in addition to starting another business (to be determined). With regard to challenges that she faces, in Maasai culture, women do not own the livestock; their husbands do, so naturally, she wants to save her money to invest in her own animals. When asked about mobile phones and how they have/haven’t helped her business, she explained that customers can ring her for produce delivery, she can be called and told when tourists are passing through town (the women all flock with their beads for sale), and when livestock goes missing, she can ring her husband to find them. This was a bit shocking to me, the way people prioritize their funds and choose "material luxuries." For instance, these women don't have running water or electricity, but they have cell phones. And in addition to a phone, she has a radio, which she was informed could provide her with information on good agriculture practices.

Namnyak and her radio

Today was absolutely magical. Parts of it even brought tears to my eyes. After a horrible night’s sleep at the guesthouse in town (really it was more like a budget hostel where I slept in a concrete cube of a room with a drop latrine that was detached from the building), I woke up at 5:45 AM. We were going to go on a walking safari at 6:30 in the morning. We walked for 2.5-3 hours through the bush, weaving in and out of acacia trees and trying to avoid being slashed open by the deadly branches coated in thorns. On the ground level, spikey protrusions greeted our legs and made one regret bearing any skin, even a patch of ankle, because of the angry burrs. Despite these botanical death traps, the walk was glorious. We set off at a “Maasai pace” (aka speed walking); I think it was the most exercise I’ve gotten in Tanzania so far (I can’t really count doing yoga, squats, and running in place in my room…). Although we didn’t see any animals, except for the occasional bird and a hare, the sun was rising and the landscape seemed to go on for miles in all directions. Apparently, we didn’t see any animals because they have been illegally hunted by non-Maasai who have moved into the area. It’s really quite sad, as elephants, giraffes, and zebras used to roam the grasslands right outside the village. The pastoral Maasai have been living in “harmony” with the wildlife for years and now the animals are being killed for their meat, which can be sold in Arusha, in addition to their ivory and hides.

Walking safari

While in town, my hosts and I each got sour milk, which is customary for Maasai culture. It sounds off-putting and potentially disgusting, but it was fantastic, like drinking tangy Greek yogurt, except that it had some creamy chunks; really it was an ice-cold “milkshake” for only 1,000 tsh ($0.63 USD).

.jpg)

Sour Milk

After we returned to the village, I helped milk again (still unsuccessful) and even assisted with preparing dinner. This was by far the most emotional part of my day. It started when we were sipping chai as the sun was setting and Ngai, one of the daughters, walked by with a bucket of spinach freshly picked from the garden. I asked if I could come watch and help. “Hodi” I called out (may I come in) as I entered their boma. “Karibu” (welcome). I walked into the kitchen, which was really just a three-stone stove in a corner of one of the mud huts. Two older Maasai women were there, Namnyak (one of the wives), Ngai, Sokoina (her brother), and four children. Despite the cramped nature of the hut, they offered me a miniature wooden stool on which to sit. The boma was really dark (no windows) and sickeningly smoky (no chimney and a face-full of carcinogenic fumes). I don’t understand how it doesn’t bother them, but I later learned that the smoke helps treat the wood against termites. At first I just watched as Ngai peeled potatoes and Namyak shredded something over the fire. Then I was asked if I wanted to help, so I took a knife in hand and began peeling a potato. Naturally, the whole room was enthralled by my show of incompetence and goofiness. At home, we have a potato peeler and a cutting board. Here, I had a dull knife and my knee. Fortunately, I’ve been trying to help Helen with meal preparation at my homestay, which has assisted in weaning me off a peeler, but it is still more difficult than it looks (as illustrated by the massive slice I made in my thumb last week). So the Maasai all watched with intrigue as I switched on my head lamp (goofy sight #1) – I don’t know how they cut in the dark with a single flicker of candle light. I was slow and keep peeling too thickly. They must have thought I was such a lazy, wasteful, and inept American; I was embarrassed. But I tried because I want to learn and get better. Ngai has been cooking since she was ten; now she’s my age. I guess this partially explains her swiftness, accuracy, and dexterity in the kitchen. I helped her cut the spinach into shreds, not realizing how much a cutting board is a crutch back home. Only about two people in the room spoke broken English, the rest Maa and Swahili. The women were adorned with ornate beaded jewelry, hanging around their necks and drooping gauged ears. I must have looked so out of place, yet I felt strangely at peace. I could barely communicate with them, but chopping vegetables, it didn’t matter. Then came the signing. Sara, a beautiful young girl no older than 8, often sang for us. Then they asked me to sing a song from home…jokes! Anyone who has heard me belt a tune knows it ain’t pretty. I froze up and couldn’t think of a song to save my life, as if all known lyrics dissipated from my brain immediately. Frantically and randomly, I squeaked (out of tune and pitch, mind you) the lyrics to “Wagon Wheel” by Old Crow Medicine Show. A stereotypical camp song and a quintessential anthem of Hamilton, I belted out:

“Rock me mama like a wagon wheel. Rock me mama any way you feel. Hey, hey, mama rock me. Rock me mama like the wind and the rain. Rock me mama like a south-bound train. Hey, hey, mama rock me.”

I don’t think they had a clue what the lyrics meant, which is probably for the best, but they seemed to enjoy it because it had “mama,” a universally recognized word. I received a warm round of applause at the end. Sitting in the boma, smoke burning my eyes, surrounded by Maasai women and children, I felt like I was in another world. It was so different from anything I’ve experienced, so strangely beautiful that it brought tears to my eyes (or maybe it was the smoke). I think these are the moments that the foundation refers to: profound and serendipitous instances of cross-culture human connection. And I don’t think it could have been more fitting than through food and cooking. I feel so different from these people: at the age of 3 or 4, young boys are out herding cattle; women must walk several miles to fetch water daily and sometimes they are forced to marry at a young age. They live in mud huts without running water or electricity, yet they seem at peace (though perhaps this is an extremely narrow minded and ignorant judgment). Though I can say with certainty that the stars here are the most amazing I have ever seen…like someone took the top off the sky and sliced open the atmosphere, scattering diamond dust; the stars have multiplied in number and luminosity as well, with very little surrounding light pollution. I can hear the faint sounds of the cow bells jingling and the occasional snort or sneeze of the livestock from the mud guest hut I am sleeping in.

My hosts here have been incredibly generous. They invited me to observed and partake in activities that most people would pay big bucks to do: learning how to milk, going on a bush walk, sleeping in a Maasai boma etc. I am just beyond grateful for their hospitality and also inspired by their good will. The woman used to be a lawyer, working for big firms around the world, London, Hong Kong etc. and after eventually establishing Testigo Africa, she is now doing what she loves. Her husband is Maasai, originally from around Ngorongoro Crater and is now training street boys in football (soccer) to help them reach their fullest potential. Her husband and I engaged in a variety of discussions ranging from corruption to the organic food movement. According to him, we need good governance if real change is going to occur, as it must be policy-based. I agree with him, but I also think that we cannot overlook the potential for grassroots action to make a significant impact. I think it has to come from both the bottom up and top down, meeting somewhere in the middle. He noted how in Tanzania, land is the problem. Organic agriculture is wonderful in theory but if they’re not applying chemical inputs, they still need natural solutions such as livestock manure. Unfortunately, it is becoming more and more difficult to raise livestock because of climate change (increased drought and decreased grasslands) and overall, decreasing land availability.

During my last day in Longido, about 30-40 Maasai women from nearby villages came together to exchange ideas about permaculture. We took a tour of the demonstration training plot, which aims to show what can possibly be grown under these harsh conditions (dry, sunny, sandy soil). According to my hosts and the translators, permaculture is self-defined, though in general, it can mean being able to utilize small spaces to grow as much as possible, especially using sustainable practices such as companion planting and nitrogen-fixing crops. It also emphasizes the use of everything available and planning systematically and in layers. The demo plot is only a little more than ½ an acre, but they are able to grow 20 different types of crops and also utilize some terrace farming to help maintain water. They explained how to prepare double dug beds, which are just raised mounds/rows for planting (either prepare compost using food remains and grass; OR collect manure, dry it in the shade for 10-14 days, and then mix it with soil to add nutrients; OR you can use vermicompost from worms (however, the volume is usually insufficient in itself). In the demo plot, they are growing spinach, Chinese cabbage, kale, beans, papaya, pigeon peas, maize, sweet potatoes, and neem trees. The use chili, ash, lemongrass and neem as natural pesticides and intercrop (e.g. sunflowers with maize, which helps the soil nutrient levels). I learned that moringa has 7x as much potassium as bananas, 10x as much vitamin C as oranges, 15x more protein than an egg; and you can dry it and make powder as a dietary supplement (which is what we did at my homestay), especially good for people with HVI/AIDS . What’s more is that moringa grows well even in dry areas. They stressed that a moringa tree should be planted in every dispensary and boma. In addition to the double dug beds, they also have a keyhole garden and a plastic-lined dam, which collects and stores water twice a year during the rainy season. Overall, the day seemed effective in facilitating the exchange of information and ideas among different women’s groups. Hopefully, it led to the creation of new visions and shown some of the challenges (e.g. on raising chickens and cultivating vegetables).

Demonstration plot

Sunset in the village

Where the cattle stay at night

Eager to sell their beautiful handcrafted jewelry

I was also eager to buy it

Training day

After a long day

Goodbyes

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

+(640x480).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment